Currently Available Artworks

Are you interested in selling or consigning your artwork?

Contact us now for a free opinion of value

JESSIE ARMS BOTKE

Jessie Arms Botke was characterized in 1931 by Los Angeles Times art critic Arthur Miller as “ample, warm, motherly; her mind vigorous as a well-rooted oak, [with] Rabelasian chuckles in her throat,” and the critical press in succeeding decades perceived the artist as the greatest decorative painter of the West. Most active in a period when the art world was almost an exclusive enclave of male artists, Jessie Botke gained extraordinary recognition through a strong work ethic and a talent that flowered rather late in her painting career. Her predilection for white birds – pelicans, geese, ducks, cockatoos, and white peacocks – inspired her to a high level of artistry.

A review of Jessie Botke’s life and artistic accomplishments reveals the portrait of a hardworking artist, irreverent in many respects, yet close to her Christian Science Church and its message – that we are “entitled to express energy, vitality, and joy.” She was forever prodding, pushing, and exploring in her attempt to gain full nourishment from life itself. Botke’s agenda constantly overflowed with her own projects and ideas, although she sought and provoked the thoughts of those around her. Apparently she required little sleep and seemed to be nourished and refreshed by her work – painting six days a week, sketching on Sundays, as well as picking,pruning, pickling, canning, reading current novels, traveling, and writing weekly to her family.

For her time, Botke was outspoken on the role of women in society and would be considered to day in the avant-garde of women’s liberation. In 1911 and again in 1912, while working for Herter Looms in New York City, she marched up Fifth Avenue from Washington Square to Central Park in the suffragette parade, shouting and demonstrating in her own inimitable fashion. Her husband, Cornelis, an artist who gained special recognition for his etchings, was usually cast in a supporting role. He often stinted on his own work to assist her with her major works, although she sometimes reciprocated by helping with his commissions. “Artist teams are much more common now than they were when we were married [in 1915],” she pointed out, adding without hesitation that “they work… Cornelis and I lean heavily on each other for advice, criticism, and encouragement.”

Jessie Hazel Arms was born in Chicago on May 27, 1883, to Martha Cornell and William Aldis Arms. Both parents were of English stock and the family tree dates to 1630, when her father’s ancestors came to Massachusetts from the Channel Islands.

Jessie graduated from Lincoln Elementary School in Chicago in 1897 and from Lake View High School in 1902; during her elementary and high-school years she spent much of her leisure time sketching and painting. In 1897 and 1898 she also enrolled in intermediate classes at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. After graduation from high school, at her mother’s urging, she decided against college and elected to pursue her career as a painter, enrolling as a full-time student at the Art Institute. Family financial reverses and the counseling and support of her mother seem to have been important factors in arriving at this decision.

At this time the School of the Art Institute was patterned on the Paris ateliers. Small in size, it provided little or no discipline or regimentation. After qualifying for life drawing, students selected their own teachers and classes; they were responsible for setting their own goals and objectives as well. In this freewheeling atmosphere the only criterion was the quality of an individual’s work. “Practice, practice, practice,” Botke noted, was the basic curriculum, with little or not emphasis on craftsmanship. In later years, she complained of this important lack in the school’s instruction, noting that students learned about artists’ materials and techniques through trial and error.

While she was enrolled at the Art Institute, Jessie made productive use of her summer vacations. At Saugatuck, Michigan, in 1903, under the school’s auspices, she attended classes in outdoor painting conducted by John C. Johansen, who was newly returned from European residence, and favorably reviewed in the Chicago press. The following summer she studied with Charles Woodbury at Ogunquit, Maine. As a result of these intensified studies, her work was exhibited at the Art Institute’s American Annual in 1904.

After leaving the Art Institute, wall decoration and book illustration became Jessie’s source of income for several years. Botke commented: “I had no training in anything but art, and so far I had no style of my own, I was completely dominated by the teachers whose work I admired so much… I kept working, and gradually my real talent began to come out, a strong feeling for decoration, two dimensional, flat pattern.”

During the next 4 years she continued to hone her skills as a decorative artist. In 1906 she made use of her entrepreneurial skills as well by bartering several paintings for a round trip ticket on the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway to Arizona and California. In 1907 she enrolled in the summer class at the Art Institute and exhibited her California paintings in the museum’s annual.

In 1909 she decided to join fellow student Dudley Crafts Watson, who was leading a party to Europe on the grand tour: Jessie’s mother agreed to accompany them as well. The trip was all encompassing, with visits to Gibraltar, to Spain, France, Switzerland, Belgium, and finally to England. They visited galleries and museums, studying both the Old Masters and the moderns.

In September, Jessie was back at work in Chicago designing friezes with a new vitality stimulated by her European experiences. In 1911, after attending a night class in architecture at the Art Institute, she moved to New York, where she immersed herself in the artistic climate of the city.

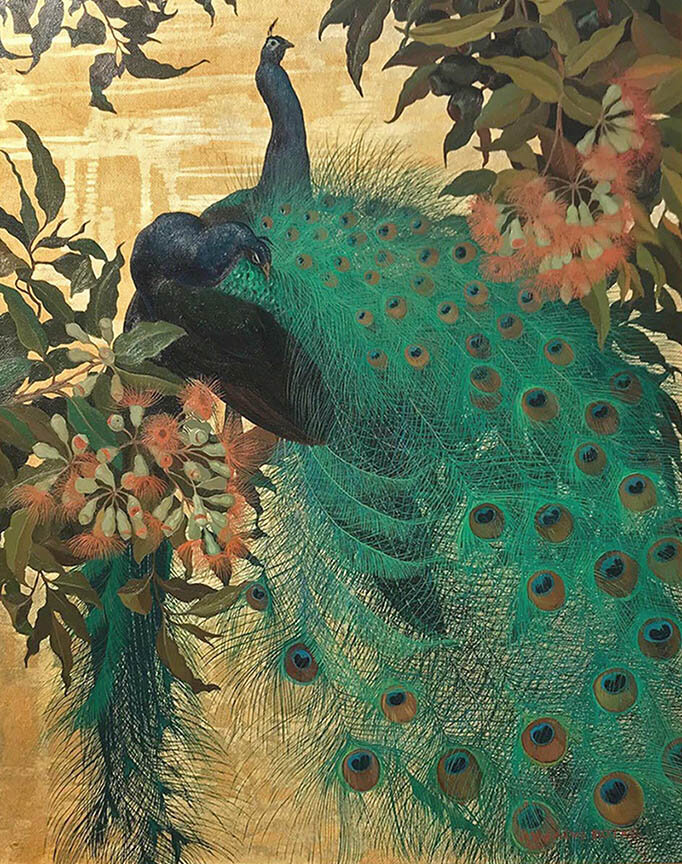

In New York she worked for Herter Looms as a designer. Her work was not confined to tapestry cartoons but included a range of decoration for interiors, including painted panels. This led to Jessie’s specialization in painting birds. When a commission was received to decorate Billie Burke’s house at Hastings-on-the-Hudson, Jessie wrote, “Mr. Herter came to me with the scheme for the dining room, it was to be in shades of blue and green and he wanted a peacock frieze using the same colors, with white peacocks as notes of accent. I didn’t even know there was such a thing as a white peacock and went up to the Bronx Zoo to find out, and they had one. It was love at first sight and has been ever since.” Asked about her love for birds in later years, she responded: “My interest in birds was not sentimental, it was always what sort of pattern they made, and the white peacock was so appealing because it was a simple, but beautiful white form to be silhouetted against dark background, and the texture and pattern of the lacy tail broke the harshness of the white mass without losing the simplicity of the pattern. For a long time I couldn’t get away from white and near white birds, geese, ducks, and finally cockatoos.”

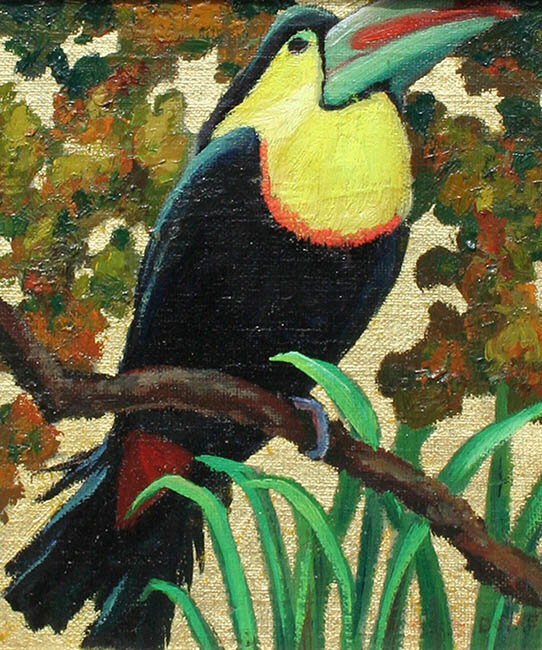

In 1912 Jessie was asked to help design a series of twenty-one tapestries woven by sixty Aubusson-trained weavers brought from France depicting events in New York City. In 1913 The Saint Francis Hotel in San Francisco commissioned Albert Herter at Herter Looms to create a series of decorations for seven wall spaces in the hotel’s great dining hall. The murals, “Gifts of the Old World”, were designed to show the cultural contributions of other areas of the world to California, and each panel had an appropriate border for birds, fruits, and flowers. Jessie Botke painted many birds for this commission, including flamingos, peacocks, and cockatoos.

After returning to Chicago in October 1914, she met Cornelis Botke for the first time, although the two young artists had heard of each other often from mutual friends. Critic Arthur Miller wrote that Cornelis “was making a living as an architectural renderer and dreaming of the day when he could paint all the time. Jessie’s style, however, was the more definitely formed and showed the more immediate promise of bringing financial reward, so they agreed that he should stay at his job until her work brought in an income and then Jessie would earn the bread while Cornelis got on his artistic feet.” They were married in Leonia, New Jersey on April 15th, 1915. In April 1916, their son, William Arms Botke was born in Chicago.

Despite the recognition the Botkes were receiving, they had become restless and considered moving to California, as had many of their friends. Hoping to broaden their careers, they left in spring 1918 for a trip to the West, arriving first in Manitou Springs, Colorado. Later in the year they traveled to San Francisco, a favorite place for Jessie. Both fell in love with California, and especially with Carmel, “the little jewel of a artist’s village in its Mediterranean-like setting.” Even Chicago’s advantages as an art center could not compete with such an aesthetically pleasing environment, and they made deposits on two lots in Carmel in 1919. Indeed, the years 1918 and 1919 were bountiful: she exhibited in the prestigious annuals of the National Academy of Design, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and the Art Institute of Chicago. In 1919 they packed up and moved to Carmel to build a studio-residence.

The Botkes were a positive addition to the Carmel scene with its thriving art colony – a haven for artists, writers, musicians, cartoonists, botanists, and many other distinguished personalities. Botke’s paintings were receiving favorable critical reviews, and they were selling well. One of her more spectacular paintings of this period, “Peacock on Gold”, completed in 1921, underscores her increased use of gold leaf in backgrounds, a technique learned at the Herter studio and later adopted as her own “signature”.

After a long and successful period in Carmel, the Botkes relocated to Los Angeles in 1928. In 1929, they moved to Wheeler Canyon, just east of Ventura and bought ten acres of ranch property. Jessie loved the ranch and with Cornelis she was able to combine fine art with farming. Botke’s artistic output and sales during the difficult years of the 1930’s resulted largely from her productivity during her residence in Carmel and Los Angeles. She had made invaluable contacts with old-line, well established galleries through her exhibitions, and she worked closely with interior decorators and designers. She received numerous awards during the thirties, including the First Prize at the Los Angeles County Fair and first prize for “Chanticleer” in the decoration category at the California State fair in Sacramento in 1934. From the early plein-air paintings, made while Botke was a student, to the graphic style of her decorative friezes and bird paintings with their fanciful landscapes, exhibited in the teens and twenties, she arrived at her fully developed style of the thirties.

In 1947 Botke began to paint small watercolor pictures, which were well received. Throughout the early fifties Botke participated in a significant number of exhibitions, and her work continued to be represented at the Grand Central Art Galleries, the Biltmore Art Gallery, the Artists’ Barn, and Gump’s Galleries. In 1951 Botke also began to compose many still lifes, undoubtedly influenced by demand and the accolades received for her prize-winning watercolor “Avocados”. 1954 was a watershed year, a year of special recognition, continuous demand for the small oils and watercolors, and a heavy exhibition schedule, but also a year of devastating loss for Jessie when her husband, Cornelis, died in September as a result of acute Diabetes.

Throughout the 1950’s and early 60’s she continued to paint and widely exhibit her works. In 1967 Jessie Botke suffered the stroke that ended her ability to paint. Four years later, on October 2, 1971, she died at the age of eighty-eight. The indomitable Jessie Botke was one of the most celebrated decorative painters of the twentieth century. From her early plein-air landscapes to her decorative friezes and imaginary scenes, she arrived at a richly intricate mature style in the 1930’s. That her work was accepted in the teens and twenties and yet remained relevant in the sixties is a testament to her staying power and the sheer beauty of her paintings.

From “Birds, Boughs, and Blossoms” by Patricia Trenton and Deborah Epstein Solon c. 1995 By William A. Karges Fine Art, Produced by Whitney Ganz.

Public Collections

Irvine Museum

Art Institute of Chicago

Sheldon Swope Art Museum, IN

USC Fisher Gallery

Fleischer Museum of American Art

For additional information about this artist visit:

Restoration of Mural by the Fine Art Conservation Lab

Wikipedia

Selection of works presented by The Athenaeum

Cranbrook Center For Collections and Research, “The Mirror”